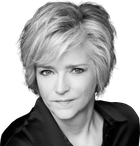

The world’s readers are finally catching up to French writer Annie Ernaux, who has been crafting intense autobiographical meditations for nearly five decades. Last fall, Ernaux, 82, received the Nobel Prize in Literature; when the news broke, she told journalists, with characteristically dry brevity, “I am very happy, I am very proud. Voilà, that’s all.” In the United States, the award sparked a heightened interest in her work—especially such titles as A Girl’s Story, about a short-lived affair when she was 18; Happening, about her illegal abortion in 1963; and The Years, a sweeping memoir that takes in decades of private and public life. This fall brings a new book—an essay, really—entitled The Young Man (Seven Stories, Sept. 12), her reflection on an affair with a much younger man when she was in her 50s. In a starred review, Kirkus calls it a “crucial addition to Ernaux’s oeuvre.” The author answered our questions by email.

The events of The Young Man took place decades before you wrote about them. How important is the passage of time for you to approach a subject? And how do you know when you are ready to write about an episode in your life?

Most of my books relate to past events in my life. I have always been unable to grasp, to understand, things in the moment when they are happening; I simply experience them, and often quite powerfully. That is where memory intervenes. For one of the epigraphs to Happening, I put a quote from the Japanese writer Yūko Tsushima: I wonder if memory is not simply a question of following things through to the end. This is exactly the function that memory plays in my writing: It brings me memories—images, words—that I then decipher as an archaeologist does excavated objects.

Most of my books relate to past events in my life. I have always been unable to grasp, to understand, things in the moment when they are happening; I simply experience them, and often quite powerfully. That is where memory intervenes. For one of the epigraphs to Happening, I put a quote from the Japanese writer Yūko Tsushima: I wonder if memory is not simply a question of following things through to the end. This is exactly the function that memory plays in my writing: It brings me memories—images, words—that I then decipher as an archaeologist does excavated objects.

The decision to write grows little by little, it does not develop overnight. Each of my texts has required a different maturation time, was sometimes abandoned, and then resumed.

This is the most recent of several books to be translated into English by Alison L. Strayer. How would you describe your collaboration with her, and what quality is most important to you in a translation of your work?

I never intervene in Alison’s translation work, but she can ask me for clarification about the meaning I attach to a sentence, or a word. What is most important in the translation of my texts is to convey their voice. By this I mean the lexical register and the sentence rhythm. Alison does this brilliantly, for example in The Years, a book that must have been very difficult to translate.

The Young Man is essentially the first of your books to be published in the U.S. since you were awarded the Nobel Prize in 2022. What kind of reception has your work received from American readers?

I don’t yet know how The Young Man will be received. The reception by the American public has evolved over the years, it seems to me, but I think that my editor Daniel Simon, the same for 30 years, is more qualified than I am to answer.

In your Nobel acceptance speech, you spoke about how important it is for writing by women to be recognized by the literary establishment. Are there contemporary women writers whose work you especially admire and look forward to reading?

There are many writers I look forward to reading each time they release a new book— Virginie Despentes, Rachel Cusk, Svetlana Alexievich, for example. But I am also attentive to new voices that are emerging.

Interview by Tom Beer. Translation by Alison L. Strayer