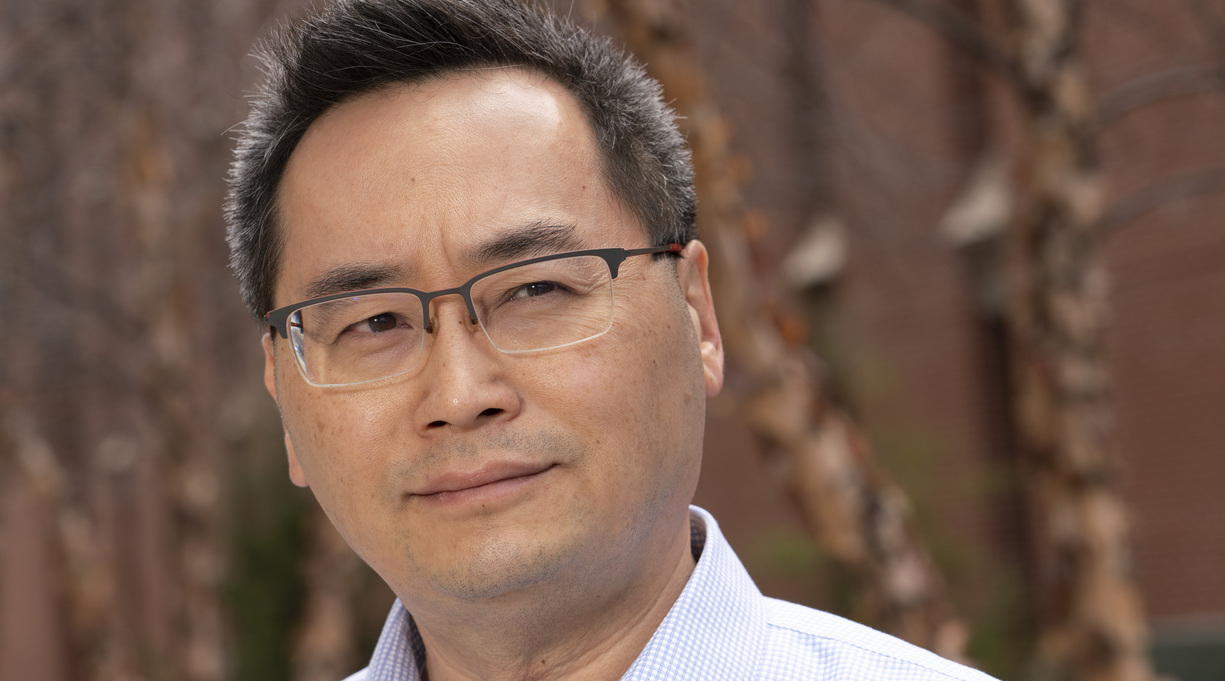

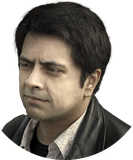

“I don’t think I could have written a memoir in the more traditional sense,” says David Shih, author of Chinese Prodigal: A Memoir in Eight Arguments (Atlantic Monthly, Aug. 15). A professor of English at the University of Wisconsin–Eau Claire, Shih eschews a chronological narrative, instead examining his life experiences as an Asian American through a series of essays, or “arguments,” as he calls them. Born in Hong Kong, Shih came to the United States with his parents as an infant in 1971, and his sense of self has transformed as the meanings of Asian American identity have changed in this country. In a starred review, a Kirkus critic calls it a “profoundly thoughtful, unflinchingly honest Asian American memoir.” We spoke with Shih, 53, on Zoom a couple of days before the U.S. Supreme Court struck down affirmative action in college admissions, a central subject of the book. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Can you say something about the meaning of the title, Chinese Prodigal?

It’s a pun on Chinese prodigy. I don’t believe in Chinese prodigies. I don’t believe that there’s anything that’s natural about being an Asian American or a Chinese American in this society—that is, there’s nothing genetic or biological or essential about who you are. Who you are is a construction, an invention. And what that does—what it did, to me, especially—is force you into a series of disguises. One of those disguises was that I really belonged in the world that I found myself in [Texas in the 1970s and ’80s] more than the world of my immigrant parents, which is why I wanted to leave it. So it’s also a little bit of a riff on the prodigal son story from the Bible—having to leave home and feeling as though that’s where you belong more. And then coming home hat in hand, if you will. In my case, with my father already gone.

Yes—you open with an essay about your father’s death. You learned that he was in the hospital, but you didn’t rush right back to see him, and he died before you were able to get there.

After my father died in 2019, I had to write about it, to deal with it. The first chapter is about my father being what I’ll call an imperfect problem solver—the way that all immigrants are. You are presented with a situation, and you just don’t have a lot of choice about what to do, when you have a family to support. You do what you can with what you have and then deal with the consequences later. Maybe that’s buying a house with a huge mortgage at a high interest rate because you need to provide for your family. I wanted to contrast that with the way the son of an immigrant—I’m an immigrant myself, but I came at the age of 1—approaches problems in a very different way. You almost revel in them, if you will; there’s a certain pleasure to thinking about problems and having the luxury of time to be circumspect about them. And that’s what I wanted to get across in that first chapter, the luxury of the way that we deal with the problems in our lives—it simply doesn’t compare with what my father and mother had to do.

After my father died in 2019, I had to write about it, to deal with it. The first chapter is about my father being what I’ll call an imperfect problem solver—the way that all immigrants are. You are presented with a situation, and you just don’t have a lot of choice about what to do, when you have a family to support. You do what you can with what you have and then deal with the consequences later. Maybe that’s buying a house with a huge mortgage at a high interest rate because you need to provide for your family. I wanted to contrast that with the way the son of an immigrant—I’m an immigrant myself, but I came at the age of 1—approaches problems in a very different way. You almost revel in them, if you will; there’s a certain pleasure to thinking about problems and having the luxury of time to be circumspect about them. And that’s what I wanted to get across in that first chapter, the luxury of the way that we deal with the problems in our lives—it simply doesn’t compare with what my father and mother had to do.

Can you say something about the form of the memoir? It’s really a series of eight essays, or “arguments,” as you call them.

Because I’m Asian American, because I’m not white, the meaning of my identity comes through these historical events that I’ve discussed—affirmative action, interracial love and mixed-race parentage, law enforcement. This is a point I often make to my students: We’re socialized to think of ourselves as individuals, but how often do we expect complete strangers to treat us as members of groups? We come to see that our identity is much more group-based than it is [based] in this sense of individuality. And so that’s why the book is a memoir in essays—who I am is because of Vincent Chin [the Chinese American man killed by two white autoworkers in 1982], because of Allan Bakke [the white man who challenged the University of California’s affirmative action policy in 1978], because of Peter Liang [the Chinese American police officer convicted of criminally negligent homicide in the killing of an unarmed Black New Yorker in 2014].

You mention affirmative action, which is the subject of one chapter and is currently on the Supreme Court docket.

A couple of weeks ago, I published a piece for the New Republic on affirmative action. I talk about a fellowship that I received [from the University of Michigan] in 1993, when I was getting my doctorate there. The name of it is great: the Rackham Merit Fellowship for Historically Underrepresented Groups. They couldn’t call it that anymore, after 2006, when they got rid of affirmative action in Michigan, but it told the truth about why affirmative action was needed in the first place—which is not diversity. I’m afraid that the meaning people now assign to Asian Americans is that we’re victims of affirmative action. If Asian Americans are honorary whites, what affirmative action has shown us is that whites now want to be honorary Asian Americans, because they can’t advocate for their privilege without a group like us as the shock troops. So, that’s a huge shift in the meaning. When I had that fellowship in ’93, I was the victim of structural racism, right? Because if there are underrepresented groups, somebody’s got to be overrepresented, but they’re not going to say that in the name of the fellowship. But within 30 years, you kind of have that flip-flopped. Of course, Asian Americans now do need affirmative action—maybe not so much East Asian Americans like me, especially middle-class East Asian Americans. But when we talk about Southeast Asian Americans, then affirmative action is absolutely necessary.

Anything else you’d like readers to know about the book?

One of the things that I really hope people get from this book is that it’s not a book about trauma. The Asian American narrative centers so much on trauma, on generational trauma, and I’m not here to say that my parents didn’t have some of that. Both of them, at different points in their lives, were refugees from the communists and the Japanese. But there was so much joy in our family as well, and I hope it comes through that they really did support me in what I want. They weren’t these “tiger parents” that people stereotypically associate with Asian immigrant parents. The book’s “arguments” are really arguments about what race means in our society. Asian American identity probably doesn’t mean what you think it does; we have to think about it in a much broader context. That includes issues like affirmative action, which means that it must include discussions of Black history. The meaning of Asian American is inseparable from the meaning of Black and white, and that’s what I want the reader to know.

Tom Beer is the editor-in-chief.